Metabolic animation

Notes on But one bird sang not

By Pierre Hébert, march 2019

I wrote these notes while on my way to the Rotterdam International Film Festival where my film But one bird sang not was to be screened in a rather unconventional setting: the Say no more thematic section that consists on four different programs each with a different accent (Say : No more distances, Say : No more straight lines, Say : No more domestic silence, Say : No more darkness). The program my film is in, was Say: No more darkness. The overall series was organized around the notions of silence, intimacy and concentration. Each of the programs was to be introduced with short wordless performances by young Dutch artists and the following exchanges with the public was to be done with unamplified natural voices in order to preserve the intimacy of the encounter and to make sure that no intervention, even the director’s, would have proeminence over the others. I found this setting quite appropriate for my film. I was very excited about all this and I feelt the need to write some notes in preparation for the exchanges with the public.

My first concern is to rectify a possible misunderstanding about the nature of the film and what «subject matter» it deals with. At first sight, it may seem to just be an abstract film aiming at a dynamic visual interpretation of a piece of music, a «visual music» piece, according to the often used expression. The relationship between my scratched animation and Malcolm Goldstein’s solo violin music is indeed so central and so closely knit that it is hard not to describe it exactly with those words : an interpretation of a piece of music. Even if I am not much at ease with the idea of «visual music», I often myself end up describing my film in such a way.

It is true that in this project, I adopted an approach where the animation is based on an extremely detailed analysis of the music. Normally, I resist doing this, I prefer to leave the development of the music and animation each in its relatively autonomous space and think of their relationship more in term of distance, resistance, centrifugal polarity, potentiality and constellation. I don’t believe that there can be a natural or fusionnal term to term correspondance between music and moving images or some kind of «pure» visual interpretationof music. This is what the idea of «visual music» is more or less based on. For my part, I strongly believe that fundamentally time does not flow in the same way with images and with sounds and that purely synchronistic connexions are based on an abstract chronometric idea of time and although it may result in very striking effects, it also tends to flatten the polyvalent richness of the connexions between the two components. So although there are in But one bird sang not a very detailled synchronized connexions between images and music, describing the film as a visual interpretation of music is a superficial statement that misses the deeper nature of the piece. Instead of the formal relations between the music and the animation, it is a better angle to start from my personal relationship with Malcolm Goldstein and his music. There are three different ways in which this is important.

a- In the film, the presence of Malcolm’s work is above all a question of documentary evidence, testifying of something Malcolm did in 1995. While the war in Bosnia and Sarajevo was raging, a violonist, Malcolm Goldstein, decides to play Bosnian folksongs as a gesture of hope for peace. It is interesting to note that the overall project, that included other songs and original compositions, was entitled : Configurations in darkness, which connects it directly to the title of the program in wich the film was to be shown in Rotterdam. We all know that such an action could not have had any real effect on the actual situation of war. Yet it is of great importance. It may seem futile and useless but it testifies about the specific and uncomparable power art may have, a power that is not bound by effects, a pure form of power that transcends the realm of causes and effects. Another example I could give is the action of watering a dead tree as seen in Tarkovsky’s Sacrifice. It could also be compared to Walter Benjamin’s idea of nonsensorial resemblances that exists but cannot be asessed in any way. Or its like an image shown in the dark or a word whispered by a deaft-mute. At the deeper level, my film is an hommage to this futile gesture acted by Malcolm years ago and a willingness to participate in its remembrance, trying to say that something very small, almost unperceivable, was resisting.

b-It seems quite obvious to me that this strange kind of action and power can only be staged by a very discrete artist, in the silence of the media. The silence of the media is almost a necessary condition for it to happen.That is to say it could not be easily attained by a celebrity or a star of any kind. Malcolm is not a celebrity although he had a very significant artistic career (John Cage, Ornette Coleman and Pauline Oliviera wrote for him and for years he toured around the world). He is now in his 80’s and lives a simple life in a modest flat in Montreal. One could think with good reasons that he should deserve more fame. But this is not really a point. Malcolm probably would not agree. His strict and purist approach to music dont depend on a wide public exposure. It is more a function of intimacy, concentration, consistency, stubbornness in staying on one’s own radical track. All things that need a certain level of secrecy. So using Malcolm’s music in a film is a very delicate operation. It is certainly taking it out in the open but with a risk of breaking something, of disturbing essential elements that have to remain out of sight. For me, working with him was part of a very personal story line. I should have met him 30 years ago when he first moved in Montreal, since he was playing regularly with musicans I knew, I should have run into him a hundred times through those years, but time has its reasons and I just met him three years ago. It was a question of age. Growing older, I found it was necessary and very gratifying to work regularly with younger artists, but at the same time it slowly appeared to me that I should also make an effort to work with older artists in order to get a sense of what it is to continue to make art late in your life keeping the same radical outlook and pushing it ahead even more radically.

c- I contacted Malcolm three years ago at a very specific moment of my creative life. I was just resuming scratching on film after 15 years of interruption. Scratching on film, a technique I learned from Norman McLaren and Len Lye, had been the center of my work for many years. I stopped in the early 2000 without really deciding, when I switched to digital technology. I have no regrets about this technological shift, it was necessary. Nevertheless, various circumstances recently led me to return to my old tools. But I was very concerned about not just going back to what I was doing fifteen years earlier and I felt I had to do specific things in order to force myself towards new directions. Connecting with Malcolm’s music was one of those steps. After studying closely some of McLaren’s work (the networks of flickering in Blinkity Blank), I came up with the idea of «polyphony of flickers». It meant constructing the film flow with complex layers of different rates of flickering and intermittences of images. Malcolm’s intricate way of playing complex arpegioslike patterns in a very elegant way but under a totally rough and scratchy appearance seemed to be the perfect fit in order to force me toward the unknown directions where I was hoping to go. I also thought But one bird sang not was a particularly beautiful piece of music. There is something at once intricate and transparent in it. Through a series of variations on a very simple theme, it reveals Malcolm’s process in an almost didactic way. This led me to do something I had never done before, something that I had claimed many times I was against, that is synchronizing my animation very closely and very precisely with all the features of a piece of music, some kind of extreme «mickeymousing». I had a strong feeling that there was a lot to learn from such an exercise and that it would force me into new territories. It was not an easy road to take, because I was resisting strongly, still being convinced of the fundamental difference between the flow of time in music and in film. I am quite certain that this is the very fact that I was forcing something unnatural in my animation that led me to accomplish what I was aiming at..

At the end of it all, I think it is a quite elegantly done visual interpretation of a piece of music, I cannot negate this and I have to admit it is enjoyable. But behind this easy going surface, there is a complex web of other concerns that have a deeper meaning. And I think it is the absolute appropriate thing that it is being shown as part of this Say: no more darkness program. It allows to reveal the complexities of the formative process of this film.

Addendum – 1

I feel it is necessary to add a bit more about this question of old age practice of the arts. As, I reached the age of seventy-five a few weeks ago, this question is becoming a central one to me. What am I trying to prove in being so stubborn in my creative life ? Luckily, here is the sheer pleasure of creation that does not exhaust itself. This is a necessary condition, but not a sufficient one. As I lived all of my adult life describing myself as an artist, a «professionnal artist», this must include, whether you like it or not, a requirement of resposability irrevocably linked to this state of being and also, I would think, beyond the question of pleasure, the obligation of a certain form of continuity of this requirement, whether the society ask for it or not. Really the society would rather tend to forget the artists that have not reached a certain level of notoriety, and expect nothing more from them. I always keep in the back of my mind the terrible admonition of the Hungarian writer, Imre Kertesz, in his book An other person :

If your occupation – let’s leave asside understatments – if the passion of your life leads you to try define the human condition, you have to open your heart to the total misery that defines this condition ; but you cannot remain indifferent to the motion of your pen, to «the joy of artistic creation». Then are you a lyer ? Of course ; but every big adventure includes this requirement : you must give away a part of yourself, let them eat your flesh and drink your blood… The worst ending is a banal, ordinary breakdown : it belies everything. You should not step outside of the limelights of the fair – oh, the horror of boredom ; boredom is a crime. (my own rough translation made from a French translation of the original Hungarian text, not to be overly trusted)

In this quote, there is the «joy of artistic creation», but also «the worst ending» that «belies everything». Since I read it. I am haunted by this radical injunction : the end of a creative life «by a banal ordinary breakdown» would contradict and deny any value to all that preceded. As if the commitment to use art to define the human condition could not suffer to be lightly interrupted without putting in doubt the seriousness and the authenticity of the commitment. When as a young man or a young woman, a person wants to become an artist because it is fun and maybe beleives to be talented, it does not appear how at the other end of the road, this decision will lead to an infernal machine from which you cannot desengage without dishonour.

What does it mean then to be forced to continue artistic creation into old age, until death or until it is physically feasable, while supposedly one does not have anything more to prove, or with a little help from agism, one is not being asked to prove anything. This brings back the question of the discreet and invisible power of art, that is outside the realm of causes and effects about which I wrote earlier, this point where the practice of art apppears as a matter of fundamental metabolism for the artist and for the society. I am refering to the minimal level of activity that must happen in an unperceivable substrate so that the organism keeps on living. Where art is a question of life an death. This is the hidden side of art, the counterpart to the fact that a work of art is necessarily an address to others, setting itself as a centrifugal vector. That would mean there is a twofold movement in art, a centrifugal movement that is a matter of sharing, and a centripetal movement that has to do with the simple fact that it is happening. The artist is at the intersection point of the two movements. And with great age, the centrifpetal, metabolistic power, normally hidden behind the centrifugal drive that, in the network of social validation, is front stage, would progressively become the hard requirement that Kertesz talks about, that puts into question the value of an entire creative life, and of which the artist can only be freed by death.

Addendum – 2

Another angle comes to my mind to approach this vision of art as a fondamental metabolic flux that sustains the continuation of life. I am thinking about a very special way to put animation in perspective that I found in a novel by the Japanese writer Yôko Ogawa, Les instantannés d’Ambre (Amber’s Snapshots, French translation at Acte Sud, 2018). I will first mention that for many years I have been a devoted reader of Yôko Ogawa and that I am highly interested by her special kind of magic realism. In my Heads project, the drawings 340 to 345 are directly inspired by the novel Petits oiseaux (Small Birds) that I was reading at the time, inspiration that kept on until the end of the series, especially at the very end with the drawings 425 to 445 (/en/visual-arts/web/heads-mail-art-on-facebook/ and also Têtes/Heads, éditions de l’œil, Montreuil, 2017, 320 pages, www.editionsdeloeil.com/product-page/têtes-heads-pierre-hébert).

In the winter of 2019, I was in Japan with the objective, amongs other things, of going through an initiation to Japanese calligraphy, expecting that it could influence my practice of scratching on film. This project came as a development of But one bird sang not, as I was pursuing reflexions about the idea of «sovereign gesture», of «absolute gesture». It was all about how to deal with the irreversibility of each stroke either in calligraphy or scratching. It also had to do with the necessity of a spiritual and bodily discipline that only can help master such irreversible gestures. That was a new episode in my program of constraints that I continue to impose on myself in order to affect my approach to scratching on film. The fact that I knew that Malcolm Goldstein was also practicing calligraphy (it is a counterpart to his musical practice that I find totally understandable as is also his habit of practicing Bach solo violin pieces), comforted me in my decision.

I was right in the middle of this learning process when I started to read the new novel by Ogawa and discovered this surprising presentation of animation. It is not easy to sumarize. Just keeping the main elements of the story, here are the essentials for the point I am trying to make : a child by the name of Amber makes his deceased younger sister alive again by animating her image on the top corner of the successive pages of encyclopedias that were previously published by his father, that have also desapeared. There are no mentions of the existence of the art of animation or of the technical conditions that normally make it possible. The word «animation» is not even used, «snapshot» is used instead. Amber spontaneously discovers the possibility to create motion simply from the vital need to overcome the death of his sister, and probably also the desapearance of his father. This happens in a context of confinement, where he lives in a bubble cut away from the external world with his younger brother and older sister. Beyond any technical consideration, animation is just shown as a simple necessity of reviving and surviving. Amber does that in the most naïve and simple way, a flip book drawn on the corners of the pages of a book. In ever ritualised sessions, he quickly turns the pages of the book with his fingers and, like a breath that blows over the encyclopedic knowledge, the death child lives again.

We also learn that Amber, as he became a very old man, living in an old artists residency, continue to show his snapshots, during special sessions for just a few peoples at the time, always from the same almost desintegrated old books. In the meantime, his art was praised by art critics, but he kept refusing that his animations be reproduced. For him, they only bear their meaning in the survival context where they originally arose.

I was very struck by this allegory of animation cinema for several reasons. First, in a context that had nothing to do with the extreme situation described in the novel, I first experienced animation by drawing on my schoolboy’s notebooks and handbooks. This is a very primitive method where the idea is to do something with almost nothing, that is not without similarities with scratching on film. Although this technique is not free to the same degree from technical considerations (it acknowledges the existence of film stock and of cinema), but because it consists of drawing directly on the surface of the film, discarding any use of cameras, it shares a similar naïve and simple approach. Reading at what degree Amber is attached to his original drawing on the page corners of his old encylopedias, I recognise the love I have for scratching directly on film stock. On the one hand, it potentially has as a substrate all of the knowledge of the world, and on the other hand, all the images of the world.

What touches me most in all this, it is that animation, beyond the historical conditions of his existence, is presented as a pure vital impulse to set alive again and to survive, implying that an action is absolutely needed to salvage oneself, on which is based all of his metabolic power. An existential reason for animation to exist, beyond its short history of just over an hundred years. Even more from the fact that it has to be an action of hands and fingers from which a breath can arrise.

Amber took the book with his two hands, put his thumb on the corner of the pages. Then, at a speed he had carefully practiced, (…) he flipped the pages at a constant speed so that each page corner be visible at regular intervals. (…) For the time of a new blink of eyelid, an image of the younger sister was revealed under Amber’s fingers. The poor unhappy child of their mother was living again in the corner of an encyclopedia within which were listed all things of the world. (…) In the instant it took for pages to flip down one after the other, Amber’s drawing could be briefly legible. (…) The three children and their mother were staying still, concentrating on listening at the younger sister’s voice, convinced that it could be heard in the breath of the turning pages. (pp 113-114, again my own translation))

Addendum – 3

In the initial section of this text, I refered to Walter Bejamins’ idea of nonsensorial ressemblance as an example of something that while having an effectiveness cannot be perceived. Several times, I came close to write off this reference because I did not feel it had a strong enough connexion with my line of thinking. Instead, I decided to read again The theory of Imitation, Benjamins’ text where this idea comes from. There could have been some good reasons why it emerged in my mind at this specific moment. This is a relatively short piece of writing but it is also very dense and vertiginous. It goes very fast from occult knowledge to the games children play, to astrology, to constellations, to the moment of birth that passes by like a lightning, to language, to the relationship between the «spoken» and the «written», to the act of reading, and finally to the rythm of reading. Overall, the focus of the text is on the nonsensorial ressemblances that are woven into language, that we do not perceive if not unconsciously. The metabolic susbtrate of the human experience of which we see only the tip of the iceberg, this is the thread that I am following. But there are other points of convergence.

Fisrt, Benjamin explains that playing games, particularly children playing games, is the school of the mimetic faculty. He returns twice in the text to this theme of childhood in relation to astrology refering to the importance of the moment of birth. Childhood thus constitue a sort of deep structure of the text. This brings me back to Yôko Ogawa’s novel where Amber’s «snap shots» first appear as simply a kids’ game. Amber draws two images of a donkey on the two faces of a cardoard disk and animate it by making it pivot at a proper speed. The next step that is animating the deceased sister is of a darker and more complex character but it still remains within the realm of games. It enters the domain of magic and totally has to do, in a singular and ambiguous way, with the domain of ressemblances. Ogawa notes that each of the singular drawings on the corner of the successive encyclopedia pages are naïve and clumsy, full of deletions. It is only when Amber manipulates the book to flip the pages at the right speed that appears like in a breath the aereal ressemblance of the little sister. This is a deep remark : animation cannot be the simple mechanical addition of successive drawings. In my opinion, the smooth animations that are the result of such a simple mechanical addition deny themselves the possibility of the magic spark of true ressemblance. The true magic of animation comes only when through a complex alchemy in the succession of drawings, something new appears, a nonsensorial ressemblance, a reminder of an archaic origin according to Benjamin, or a reminder of the world of the deads, according to Amber.

This maybe is the deep meaning of the famous Norman McLaren’s defenition of animation (Animation is not the art of drawings-that-move but the art of movements-that-are-drawn). In a way, the following quote by Benjamin, deals with something similar.

The tempo, the speed of reading or of writing – element that cannot be dissociated from those activities – thus represented in a way the effort and the capacity unfolded to make the mind participate to the rythm according to which ressemblances spring fugitively out of the stream of things, briefly spark and falter back in the flow. So, unless one accept not to understand, profane reading has in common with magic reading the fact of relying on a necessary rythm of reading, or more precisely on a critical instant that the reader should not at any price neglect if he does not want to be left with empty hands. (my own personnal clumsy translation from the French translation in Revue d’esthétique, numéro hors série consacré à Walter Benjamin, 1990, pp 61-65).

This applies to animation, and most particularly to the special type of animation I designate as «polyphony of flickers». In this case, a simple look at the series of images does not allow to perceive what will appear only when those images are projected at a certain speed on a screen. What becomes visible then is exactly like the ressemblances that «spring fugitively out of the stream of things». They are «images» that are only visible in their flux and that are impossible to freeze. For example, I did not draw any bird in But one bird sang not, but you may see a lot of them that spark in the flux of animation.

I find also other convergence with what Benjamin writes about the relationship between the written and the spoken. He stresses the importance to consider the history of the formation of writting, and mentions the lessons of modern graphology on this matter. But he does not go as far as to consider the case of Chinese ideograms where we can find an established history of how the characters first appeared, based on clear resemblances with things of the world and related to a cosmological system and a theocratic political framework. And how those resemblances faded away through a process of secularisation, of schematisation and of simplification, and also of agregation of multiple components. Not forgetting the history of calligraphy itself that followed step by step this process toward abstraction, where the tension between the spoken and the written is doubled by the tension between graphic invention and legibility and where the profane meet the magic and the ritual. So from a simple interest in «sovereign gestures», in the aftermath of But one bird sang not, I now find myself in the midst of an historical and cultural maelstrôm, unexpected and vertiginous, off wich I don’t know how and when I will emerge.

Addendum – 4

The dream of a bird that does not exist

Is of not being a dream anymore

Nobody is ever satisfied

How is it possible that the world

Goes well under those conditions ?

Claude Aveline (again, my poor tranlation)

All those considerations about But one bird sang not, make me think to Robert Lapoujade, one of the animation filmmakers that I admired at the beginning of my carreer, and to his film, Trois portraits d’un oiseau qui n’existait pas – Three portraits of a bird that did not exist (1965, ORTF, from a poem by Claude Aveline, music by François Bayle). Because of the «bird» of course ; because of the reference, in both cases, to a negative wording, «that did not exist» on the one hand (although he makes three portraits of it), «sang not» on the other hand ( although the film makes is song heard) ; because of the initial segment of the film that remind of Blinkity Blank (where it is also question of birds, also with Amber’s aerial animations ot the little sister) ; because of the third portrait where the animation delicately touches the domain of intermittence, where the complex frame by frame constructions become on the screen «images that do not exist» that are only allowed to spark by the unfolding of the film strip.

I mention the name of Lapoujade because I never forgot him and because, since he passed away in 1993, (for many years, he had been living in extreme destitution, according to Pascal Vimenet’s testimony in Abécédaire de la fantasmagorie – Variations, pp 157-161), his commited work as a painter and as a filmmaker was almost forgotten. Most of his films remain inaccessible, stored somewhere at INA, and have not been projected since a long time. Only Trois portraits d’un oiseau qui n’existait pas is available on the web. His work is submerged in the sillent and metabolic underworld of the history of art and cinema with all those other lost works that secretely and unconsciously nourish us.

Yet, in 1965, in an important article, «Résumé du chapitre suivant» (Cinéma 65, Spécial animation 2, pp 91-104) the french critic André Martin, in trying to define what was promising in the world of animation cinema at the time, included the name of Lapoujade along with those of Norman McLaren, Len Lye and Robert Breer. About Norman McLaren and Len lye, Martin declared that they had «touched to the cinema», stressing the fact that they worked without a camera. But one can say that with his lenghty commentaries about the extreme use of discontinuities by Robert Breer, it is possible to extent the use of this idea of «touching to the cinema» to the complex domain of the modulations and the permutations of the space between frames. This allow us to situate the subtle work of Lapoujade in the territory of what «touches to the cinema», simultaneously a bit beneath (the first portrait), and a bit beyond (the third portrait) of the mainstream practice of animation. His use of discontinuities expresses itself with a degree of reserve that places him in the opposite extreme of the axis that relates him to the frenetic charater of Robert Breer’s films.

It is to be understood that I am trying to put in order my personnal pantheon of those who illuminated the beggining of my carreer, which includes André Martin. It is interesting to note that at the moment when he was desapointed with the course of things in the world of animation and was busy rehabilitating the tradition of the American animated cartoons, it seems that Martin nevertheless felt forced to draw great attention to the work of the discontinuous and this even in relation to the history of classic American animation : Please be aware that the creators of the animated cartoons tradition have always held the stage of «rough animation» as the most beautifull of all. And that they were sad to see their work submitted to the industrial process of cleaning where all the unruly aspects of the initial spontaneaous drawings were erased at the profit of a smooth sterilized perfection. (opus cité, John Hubley, un anarchiste de sang royal, p. 26, my translation). In another part of his famous définition, McLaren evokes the possibility of manipulating the invisible : Animation is therefore the art of manipulating the invisible interstices that lie betwen frames. Maybe is it possible to see here, with Martin, the origin of the «power of animators to espress directly the human thought with dynamic images». Maybe we find here a path that allows to define a specificity of animation in relation to live action cinema that goes beyond the unsatisfactory alternative between fantasy and realism, be it ontological, and situates itself in direct relation to human thought, legitimising animation as a complete part of cinema. I wrote extensively about this in my text : André Martin et André Bazin, ontologie du cinéma, (pierrehebert.com/fr/andre-martin-et-andre-bazin-ontologie-du-cinema/ or www.horschamp.qc.ca/spip.php?article784).

Addendum – 5

I am now reading Les Combarelles by Michel Julien (éd. L’écarquillée 2017), a book about prehistoric cave art. This is propulsing me towards many other ramifications in the constellation of images that surrounds my practive of engraving on film. When I was 19 years old, at the moment of my first trials, I was happy to compare my decision to engrave directly on film with the thousand years old decision to use a rock face as a surface to draw on. And it involved also the gesture of engraving on a surface that was offering resistance. I was also seing analogies between my gesture of scratching on film and the gesture of the archeologist scratching the ground to discover the past under layers of dirt. At the time, I was a student in anthropology particularly interested in archeology and I was obsessively trying to find thousand years old roots to my first steps in cinema.

The cave of Combarelles that Julien comments on, does not have colours, only lines engraved in the stone walls. Those engravings is what touches me most. I was also very inspired by the engravings on stone walls at Foz Coa in Portugal. I used some of them in my video installation and film Berlin – The Passage of Time (2014-2018). It is enough to have a look at the black and white renderings of the Combarelles engravings, on the first and last pages of Julien’s book, to readily see the importance for me of those memories of prehistoric cave art. One could beleive it was scratched on film.

But Julien’s book also interested me for another reason that I was not aware of until now. He notes that «cave men» were not dwelling in caves, a well known fact. They visited them for other reasons, like painting, drawing and engraving pictures of animals on the rock walls. It happens that, for reason that we will probably never fully understand, they generally went to the further end of the caves to make their art. They had to crawl through narrow passages and get involve with the risk of running into unwanted encounters, of getting lost, or of getting caught by sudden floods. A corollary to this is that it was equaly as hard and dangerous to go see the artworks. It was impossible to visit them easily and frequently and they were not made, in all likelyhood, to be made constantly visible for large numbers of people. It seems that it was enough that they existed out there in the dark to bear the metabolic force that I am discussing here. It is quite ironical to note that after their contemporary discovery and acessibility to crowds of curious visitors, the caves generally had to be thightly restricted, in Lascaux for exemple, in order to prevent the fatal decay of the colours.

…in closing up Lascaux, we are admiting that the caves were not fit for so much precipitated activity, we give them back the idleness for which they were conceived, their forsaken equilibrium, because even at the time of Magdalen they were made to remain in solitude (…) We suppose that they seldomly visited them. From the ouside, they knew that there was this place so near that bore those undeniable occulted representations, exactly like now we know that famous frescos are enclosed in the ground, that we cannot contemplate. (p.63, my translation)

To satisfy the touristic pulsion, imitations were built just ouside the real caves, that can be visited without risks. I cannot refrain from thinking that although the reproductions are very precise, something essential remains imperceptible to the queue of visitors that walk in front of the reproduced images.

What is troubling when we come near a cave with paintings and engravings, it is not the fact that we don’t understand their general meaning, but rather the fact that we have the intuition that in similar circumstances we would have done more or less the same thing. We would have also crawled with the absurd project of offering our gestures to the darkness, without any necessity, a major and clumsy form of our mind…(p. 75)

It also makes me think of a passage I read, many yeares ago, in La pratique de l’art, a book by Antoni Tapies (Idées / Gallimard 1974. Pp 269-270). In a totally different context, Tapies relates the following :

The Japaneses know very well that in order to have an object of art fulfill its function, it must be surrounded by a certain solennity, by a certain respectful mystery. This is why they keep all of their objects hidden and only take them out when they know they will receive the attention they desserve. Then a case of an admirable simplicity appears to be contemplated. Then a package is taken out, wrapped in a precious cloth, folded and knotted with refined care. The mystery and the haste to see is increased by the admiration. And one experience the emotion of seing the pure existence of things, as if it was for the first time. (my translation) And so on, Tapies continues to describe step by step the long process of unveiling the work of art until the final moment of meditative contemplation.

There are huge differences between this refined ritual and the fact of crawling in a cave, but in both cases, the act of seeing is put in a set up structured by two opposite forces : the simple hidden existence of the work and the conditions of its visibility, a centripetal vector and a centrifugal vector. It would seem that the moment of exhibition cannot be without an equivalent moment of concealment. And also it would seem that if bad circumstances result in the reclusion or the oblivion of a work, it does not lose the metabolic force that comes with the simple fact of existing or of having existed. Realizing this, it seems to me, is also an inevitable and priviledged part of the experience of becoming an older artist.

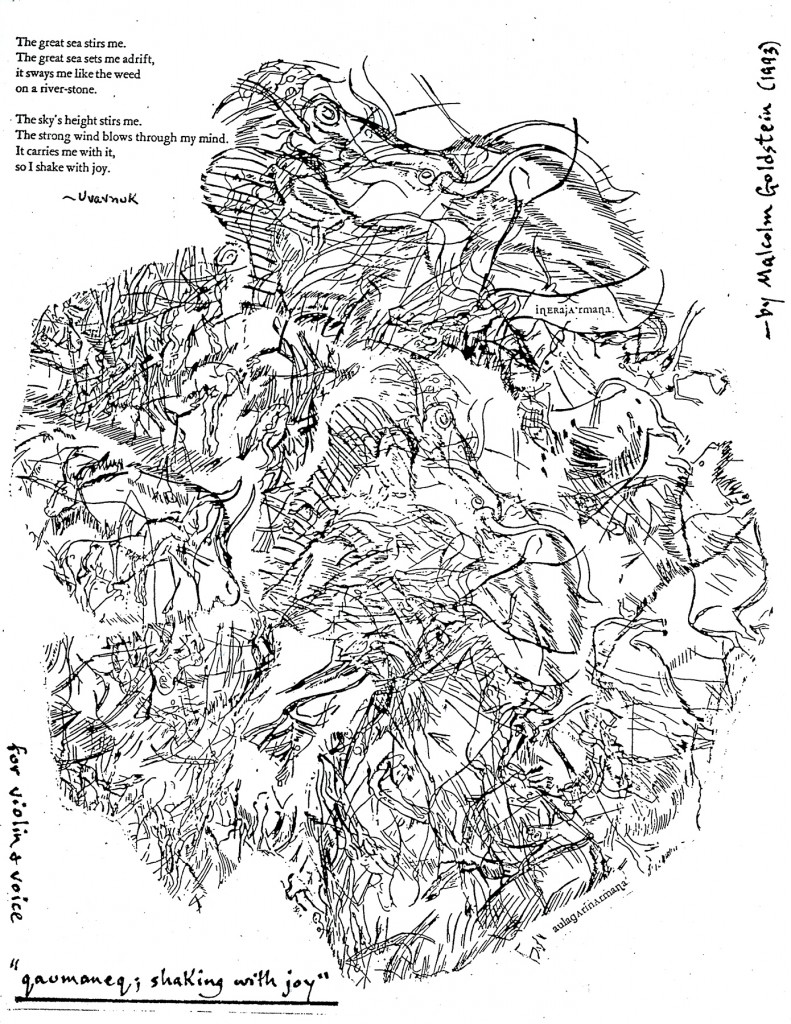

Graphic score by Malcolm Goldstein (Gaumaneq; shaking with joy, 1993 for violon and voice) inspired by an Innuit poem and based on an assemblage of diverse parietal prehistoric engravings.

Addendum – 6

I finally think to Jim Magee, an American artist whom I had the honour and the pleasure to meet once, some twelve years ago. For more than thirty years, Jim has been pursuing a secret and solitary art project entitled The Hill, in the desert of Texas, at some distance from El Paso. It consists of a group of four stone buildings, positioned in the form of a cross, like some kind of ceremonial mausoleum. Each of the four structures are filled with complex scuptures made of welded scrap metal, broken glass and all sorts of other found material. The complex is located in an isolated place in the desert, not visible from the nearby road, and is not open to visits except, occasionally, on invitation by Magee himself. Due to questions of health and age, Magee has let himself convinced to the publishing of a book of texts and photographs about his project, James Magee – The Hill (Nasher Sculpture center et DelMonico Books, 2010). Simply looking through the pages of the book is already a rare experience.

Jim Magee has been taking people he likes and trusts to the Hill since the late 1980, when he first began working on the buildings. These groups vary in size from one to four, with an occasionnal larger gathering. Since the Magee Hill is – and has been for more than twenty years – «in progress», with active work taking place in one or the another of the buildings, each visit depends on the exigencies of that work. And each visit is an emotional journey for both Magee and his handpicked visitors, beginning with their long ride through the desert. Since he began to fill the buildings one by one with works of art, he has created narrative sequences for the visit that, like all succesful narratives, gradually gain power and emotional gravity as they progress. When his tour is finished – and the duration of each tour varies – he releases the visitors to the silence of the desert and to their thoughts. He simply walks away… Richard R. Brettell (p.103)